This

week I made a trip down to Raleigh to visit my friends back in the office. It was a time to catch up on what is going on

in their lives and hear the latest news.

It reinforced how much I miss those folks.

The

trip also gave me an opportunity to look through some old issues of Wildlife

in North Carolina, the agency’s national

award winning magazine. I read through copies back to 1947, but focused on one from 1968 in which Lewis

Barts was highlighted as the Wildlife Protector of the Month.

Lewis

was the officer in Cleveland County where I grew up. I would like to say that I heard lots about

him growing up or that I had an encounter with him while hunting of fishing

that led to me becoming a wildlife officer.

But, none of that applies. I

hunted out the back door as a kid and only fished in farm ponds. Later, as a teenager, I hunted in the surrounding

counties and trout fished in the mountains.

|

| Lewis Barts Protector of the Month - Jan. 1968 |

But

after working a few years as a wildlife officer and moving down to Rutherford

County, I begin to hear stories about Lewis.

He referred to most people as “cowboy" as in, "Let me take a look at your license cowboy." How, he ate breakfast most mornings

at Don’s Pancake House in Shelby where future country singer Patty Loveless waited tables. About his service as a sniper in the South

Pacific with the Marine Corp during World War II (he was awarded the Purple

Heart for being wounded in action). Retired Captain Bill Townsend

worked with Lewis during Bill’s early days as an officer. Years later, Bill and I were working together along the Dan River and had a verbal confrontation with a loud mouthed, bully type. As we left the guy fuming over a littering ticket, Bill said, “Lewis Barts would have pressed

that guy into either fighting or backing down.

Lewis would’ve seen what he was made of.” Bill later said that Lewis wasn’t scared of

anyone or anything.

Thumbing through those old magazines, it was obvious that our agency and division have

always had a variety of characters like Lewis – if nothing else you can tell by

the angle of their hats. But just being

colorful doesn’t necessarily equate to having impact.

The

recovery of our deer herds, turkey populations, bear numbers and a number of

other species can be directly traced to men like Lewis diligently enforcing the

game and fish laws. Their impact on the resources

are obvious as you look back over a span of time.

|

| District 4 officers prior to a night deer hunting detail - late 1940s |

|

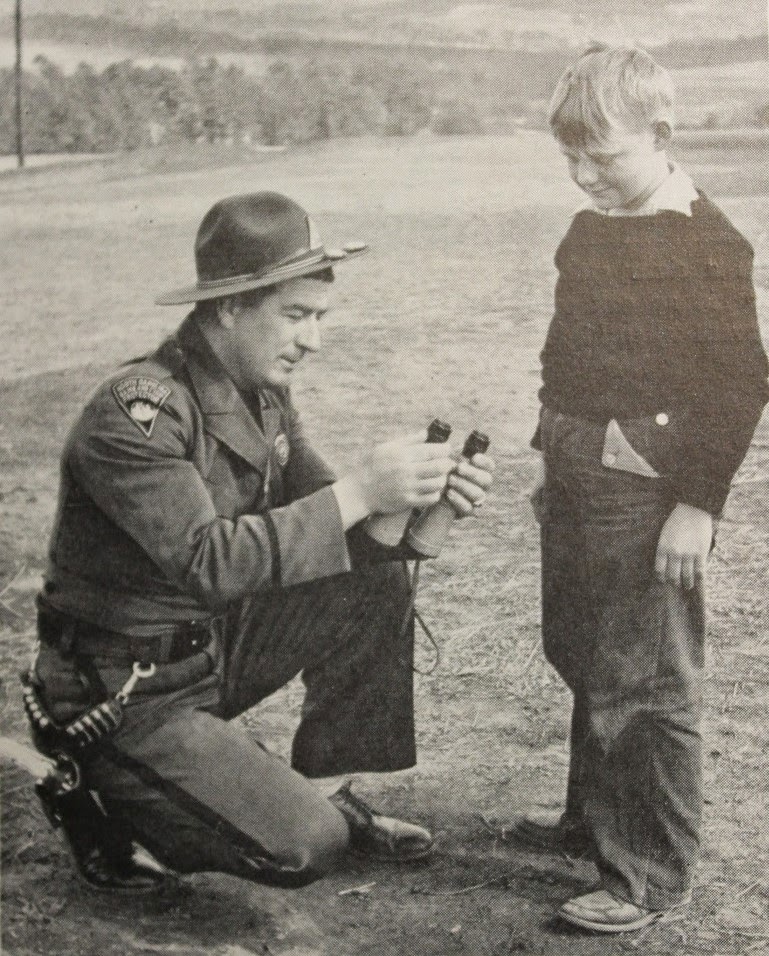

| Officer helping boy with binoculars - 1951 |

An impact that is more difficult to measure is that made by officers with the

people in their communities. Field

officers encounter an extremely high number of people over the course of their

work week. Some are through compliance

checks, arrests, or during educational programs. Most are casual encounters at a local store,

garage, courthouse or any other the other countless places where officers have

only a brief interaction that is usually quickly forgotten by the officer. Some of these “casual” contacts make a

lasting impression on the public.

My

only contact with Lewis came after I had applied to become an officer. He called me and setup a time for us to meet at

the Highway Patrol station in Shelby. He

passed along a packet of information that I needed to fill out to move me to the

next round of the selection process. He also gave me an overview of what to expect

as I moved through the various stages.

Lewis retired a short time after that evening and I never saw him

again. He was succeeded by Chester

Ragland who later became my sergeant.

I

realize that that packet would have been delivered by someone else if Lewis wasn’t available. So, it isn't accurate to say he is singlehandedly responsible

for me being hired by the agency. But,

his willingness to take on this mundane task helped launch my career. “Just another day” for him was a pivotal moment

in my life.

No comments:

Post a Comment